What is Value Investing?

ORIGINS OF VALUE INVESTING?

This way of investing dates back about 100 years but remains to this day a highly regarded strategy with proven results. Benjamin Graham, American economist and investor is the original creator of value investing. However, it was not until 1934 with the publication of his book 'Security Analysis' that his investment theory was made known to the general public.

The book was a real 'game-changer' for the time because of the logical and rational way in which the investment process was mapped out. Graham (and co-author David Dodd) were the first to separate investing from speculating, until then there was precious little structure or consistency in the way investment decisions were made.

The duo of Warren Buffet and Charlie Munger are undoubtedly the most well-known supporters of value investing. Their tremendous successes are part of the reason for the popularity of this value approach.

WHAT IS VALUE INVESTING?

Simply put, the value investor specifically looks for companies whose market value (stock price) is lower than their current intrinsic value.

Some key terms in value investing that are important:

- Market value: the value that the company is being given by the market, i.e. the current price that market participants are willing to pay for this company.

- Intrinsic value: this is a calculation of the actual value of a company and is completely separate from the actual market value. A distinction is made between:

- The intrinsic value of the company: This amounts to the company's equity, being its assets minus its liabilities.

- The intrinsic value per share: This is calculated by dividing the intrinsic value by the number of outstanding shares.

- Overvaluation: When the market value is higher than the intrinsic value, this means for value investors that the company in question is overvalued and the shares are therefore too expensive.

- Undervaluation: When the market value is lower than the intrinsic value, this means that the company in question is undervalued and the shares are therefore cheap.

By comparing this intrinsic theoretical value with the current market value, it can be determined which companies are over- or undervalued.

Value investors focus on stocks that are undervalued because they expect the price to rise again since the company is worth more than the current market price (based on the calculated intrinsic value). The greater the difference between the (lower) market value and the (higher) intrinsic value, the more interesting the stock becomes for the value investor.

Yet it does not stop here. After all, it is not that stock prices will automatically rise because the current market price is lower than the calculated intrinsic value. In order to value the future real value of a company, one will also have to look at the expected growth and revenue, the profit development, the value of the brand, the general entrepreneurial climate and the quality of the management... Determining the intrinsic theoretical value is only one - admittedly important - part of a more detailed and complex way of assigning a specific future value to a company.

A few popular valuation models:

- DDM (Dividend Discount Model): A quantitative method in which the fair value of a company is determined based on expected dividends.

- DCF (Discounted Cash Flow Model): One of the disadvantages with the Dividend Discount Model is that it is only applicable to dividend-paying companies. The DCF model, on the other hand, is applicable to both dividend paying and non-dividend paying companies. The model uses discounted future cash flows to value the company and tries to predict the free cash flows for the next 5 to 10 years.

However, there are also subjective elements that need to be taken into account. For example, how do you value a "brand name" or "the quality of its management"? In what way do you take into account "changing market conditions" or "new social trends" that may have an impact on the company?

MARGIN OF SAFETY

Precisely because there are many pitfalls and assumptions when valuing the real value of a company, value investors build in a Margin of Safety into this investment strategy. It acts as a kind of buffer between the intrinsic value and the prevailing market price. How much that Margin of Safety should be is different for each investor. Moreover, the accuracy of the Margin of Safety used is highly dependent on how well you can determine the intrinsic value of a company....

An example: Suppose you have determined the fair value for company X at $50 and you use a margin of safety of 25%. The stock is currently quoted at $44. The fact that the current market value ($44) is lower than the fair value you have calculated ($50) indicates at least that we are dealing with an undervalued stock. However, with the margin of safety used, you may only buy this stock at a maximum price of $37.5. ($50 -25%).

Now, for the sake of simplicity, let's assume that the stock did indeed sag a bit further and your limit price was hit. So you bought shares of company X at $37.5. 18 months later, the stock is trading at $43 and you find that your previously calculated growth forecast was too optimistic and the current market value is more or less equal to the fair value. However, because you took into account a margin of safety when buying (shares bought at $37.5), you still realize a profit of almost 15% (current value at $43).

If you had not used that margin and simply bought the shares when they were quoted at $44 while you had calculated an intrinsic value of $50, you would have been confronted 18 months later with a share price that was quoted $1 lower ($43).

Such a margin of safety gives a little more flexibility in terms of the accuracy of your calculation of the actual value.

WHERE DOES THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN MARKET VALUE AND INTRINSIC VALUE COME FROM?

This has everything to do with investor sentiment and the general stock market climate. Price fluctuations in a stock price (especially for the short term) never reflect the true value of a company. Moreover, it is impossible to measure sentiment and emotions, something that is possible for the actual value of a company up to a certain point and with the necessary safety margin. That is also why value investing should always be considered in the long term. In doing so, even as a value investor, do keep in mind that irrational stock prices can last much longer than your ability to be patient....

Just like the overbought and oversold zones of technical indicators, the concepts of 'undervalued' and 'overvalued' offer no assurance that the price will rise or fall. Price is still determined in the short term by supply and demand and not by actual value. As a result, shares can fall far below their intrinsic value but, conversely, shares can rise far above their real value. So, as a value investor, don't be too quick to sell shares and take profits off the table just because they are quoting well above their intrinsic value. By doing so, you are almost certain to miss out on exceptionally large price gains.

WATCH OUT FOR THE VALUE TRAP!

Value traps occur when the share appears very cheap based on your calculation but where the real value is ultimately much less than what you had calculated. However, do not confuse this with shares that have fallen heavily in price for purely speculative (technical) reasons but whose fundamentals are still solid.

Causes of Value Traps:

- Cyclical stocks: These are stocks of companies that typically do well when the economy as a whole is also performing well. However, as soon as the economic engine starts to cramp, cyclical stocks are the first to suffer, resulting in decreased earnings and sales. So if you buy cyclical stocks just before an economic dip, there is a good chance that you will not enjoy them in the near future. The only bright spot is the fact that an economy eventually recovers and so do cyclical stocks.

- Be careful with intellectual property: Patents on certain products can be very lucrative but if the profits of a company largely depend on them, this is a risk that should not be underestimated if the company loses the patent protection. These are typically found in the pharmaceutical sector.

- Fraud: A rather obvious reason why shares perform much less than what you had predicted occurs if the figures on which those assumptions were made are simply wrong because they were deliberately manipulated and embellished. On paper and to the outside world the company appears to be a bargain, in reality the situation is much less rosy. Once this comes to light, it is obvious what this does to the share price... Examples such as AIG (2004), Freddie Mac (2002) and Wells Fargo (2017) are well-known.

- Changing market conditions or a change in the public perception: A very relevant example of changing market conditions is the ever-increasing market share of online shopping compared to physical stores. Companies that have not yet reoriented themselves in this regard are falling behind and will eventually disappear from the scene, no matter how good their historical track record may be. Evolving social insights can also indirectly influence the future of a company. The worldwide increased attention for the climate and the related global energy transition that we are currently experiencing will undoubtedly ensure that old industries are doomed to disappear in favor of new, more sustainable technologies.

ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF VALUE INVESTING

Advantages

- This method of investing requires little follow-up once the shares are purchased. It is a fairly passive, quiet investment method whereby transaction costs barely affect the return.

- Due to the passive character and the incorporation of a margin of safety, you are better armed against volatile markets.

- The companies that are interesting for value investors usually also pay a dividend, in contrast to investors who opt for typical growth stocks. In addition to the dividend, you also have the prospect of stock price appreciation.

- When the dividend is reinvested, value investing is one of the best ways to grow your portfolio exponentially.

Disadvantages

- Selecting the right value stocks takes time and knowledge, determining an intrinsic value is not an exact science because it depends on a lot of factors, not all of which are objectively measurable. Besides the financial data of companies and comparing them with other companies in the same sector, other factors must also be considered in the decision-making process, such as changing market conditions and/or evolving social perspectives.

- Despite careful preparation, there will always be companies that never reach their full potential despite their undervaluation. The invested capital may then be unavailable for a long time. The decision whether to sell the shares or wait a little longer is a difficult one in such cases.

- Patience is a beautiful virtue.... Especially with value investing. If you are more of an active investor type, this form of investing will be less suitable. Value investing requires a mindset that is more focused on 'investing' than 'trading'.

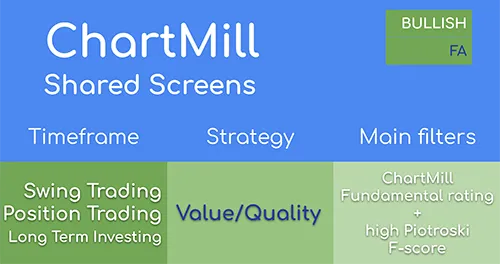

FINDING VALUE STOCKS USING THE CHARTMILL STOCK SCREENER

In this article we show you how to use ChartMill to get a first selection of value stocks that might be of interest.